Why should you trust the scientific method? What makes it any better than a great idea from someone you respect?

I’ll share some excerpts from my book (Why Stuff Falls Down), and you can see what you think!

The essential foundations of modern science are rational thinking, critical thinking, and empiricism.

“Rational thinking” means that you check to see that your thoughts don’t contradict each other. “Critical thinking” means that you verify your thoughts and beliefs against real-world data. “Empiricism” means that you have more confidence in real-world observations than in stories that you make up in your head (or that other folks put into your head).

Empiricism is putting more trust in what you actually encounter in the world, than in whatever it is that you might dream up in your head. The results of physical experiments are to be trusted. Ideas or attitudes that are in conflict with real-world experience are to be questioned.

Rational thinking means that you compare one of your thoughts or beliefs to all of the other thoughts and beliefs that you hold to be true. If there are inconsistencies, you question the thoughts and beliefs that are in conflict. Your actions are also part of this picture. If you act one way and think another way, then either your thought or your action is irrational.

Rational thinking means that you strive to have a worldview that is not in conflict with itself. Your thoughts, beliefs, and actions should be logically consistent.

Critical thinking, on the other hand, means that you hold your own convictions up to the light of day. You actively question whether those convictions are justified by the facts at hand. Rather than just trusting what feels right, or what you have been told is The Truth, you examine whether your convictions are in accord with what actually goes on in the world.

Skepticism requires that you hold off judgement until the facts are in. To be skeptical is to suspend belief in what you are being told, or in what you think about a situation, until there is convincing real-world evidence. Skepticism, and an openness to questioning your own beliefs, are the hallmarks of critical thinking.

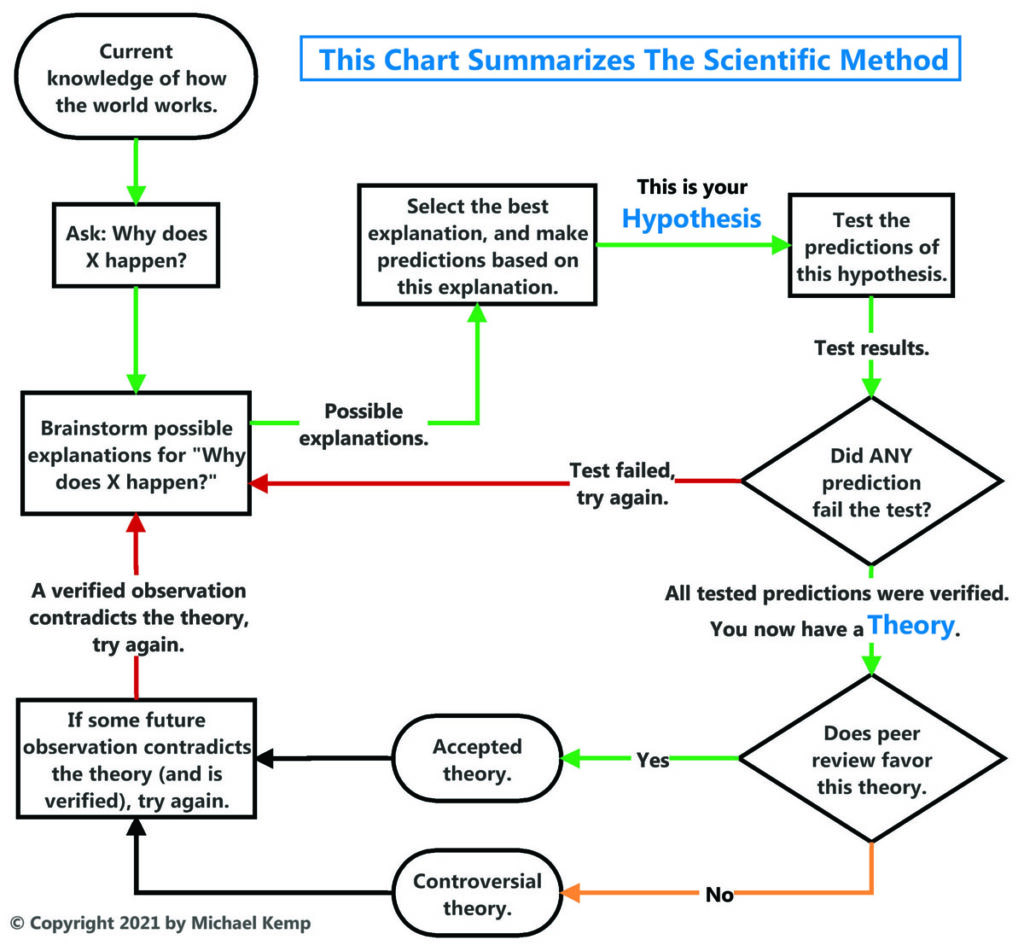

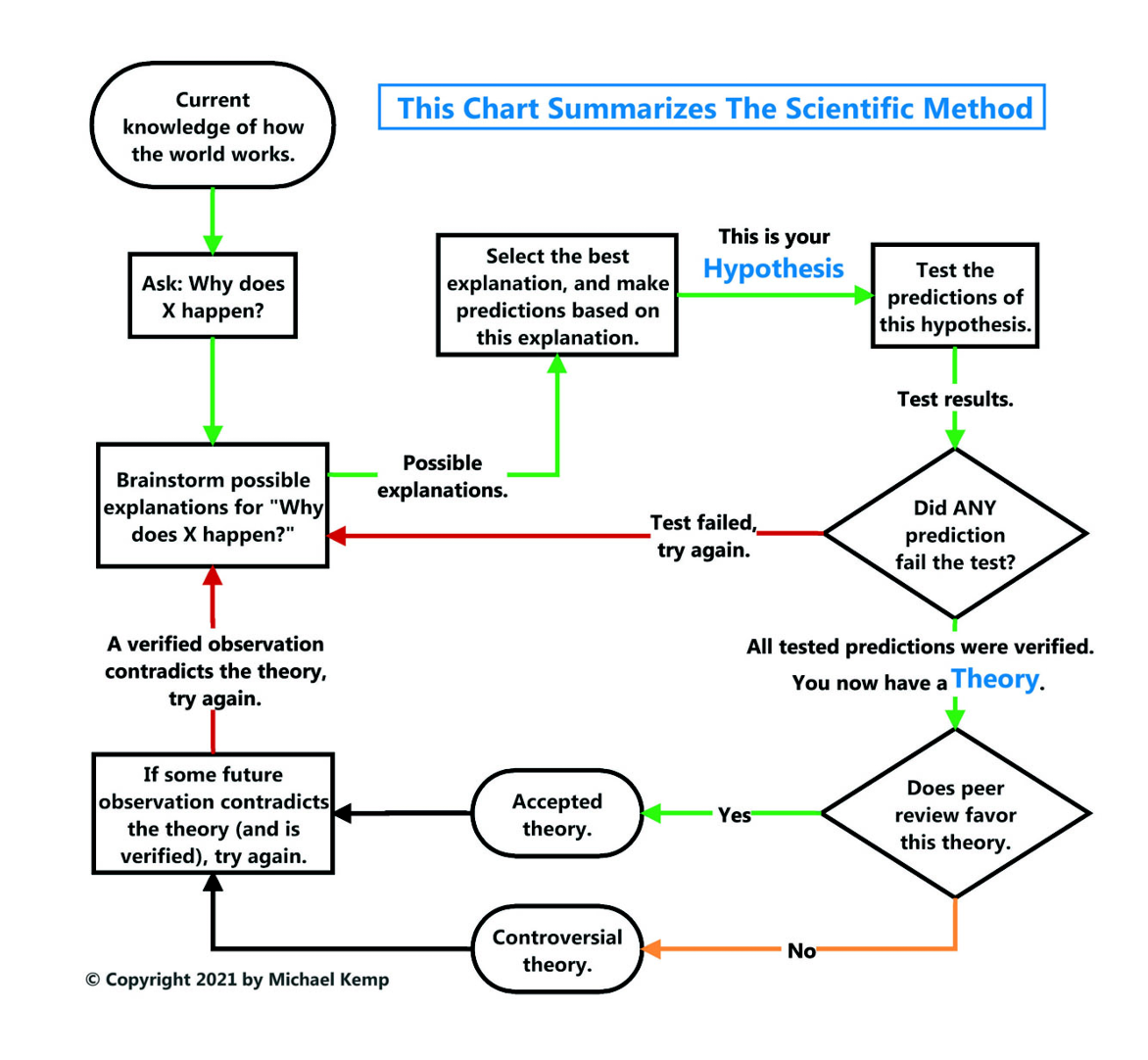

Here’s my $1.00 tour of how the scientific method works (the bullet point version):

- Form a question about some natural event or observation.

- Make some guesses about what the answers to that question might be.

- Compare your guesses against existing knowledge, then pick one guess that matches all the available data. You can call this a hypothesis.

- Any hypothesis that can be taken seriously must make unique predictions. Those unique predictions must be so clearly stated that they can be tested in the real world. When a physicist says that “a theory must be falsifiable” that’s their fancy way of saying that it must make specific enough predictions that testing can show whether the prediction is true or false.

- If the result of testing of any prediction of a hypothesis shows that prediction to be false, then the hypothesis is disproved. At that point, the hypothesis must be discarded or revised.

- If all of the results of such tests agree with the hypothesis’s unique predictions it is well on its way to being an actual scientific-method-certified theory.

- To share a new theory with the world, the researcher(s) write up a paper describing the theory, its predictions, the tests they have run, the data they used, and how they analyzed that data. This can be posted as a pre-print to an online site like Cornell University’s arXiv.org.

- To become really official, the researcher(s) will submit their paper to a respected and specialized journal such as Science. The journal’s editor will forward their paper to two or three physicists working in the same field. This is peer review. These reviewers look for originality, logical consistency, clarity, the validity of the test data, and the validity of the methods used to analyze it. If the reviewers tell the editor that the paper passes muster, the journal will print the paper. If not, the paper may be rejected or sent back for revision. It can take as much as a year before the paper will actually be printed. The journal Science only prints about 8% of the papers that it recieves.

- Once the paper is published (either in a journal, or as a pre-print), scientists around the world can look at the logic behind the theory and try to replicate the test results of the theory’s predictions. The more tests that are performed, and the more respected scientists there are performing those tests, and the more consistent the results of those tests are — then the more convincing those test results are, either in supporting or disproving the theory.

As far as proving a theory, there are proofs in mathematics and there are proofs in logic but there are no absolute proofs in science. The best that you can get from the scientific method are theories that are well supported by experimental results and are accepted by peer review.

I’m also here to tell you that “The Truth” is not to be found in science. The scientific method is all about observing and questioning and testing and questioning all over again. The goal of science is to understand how our universe works, not how we want it to work.

This is an important distinction, which split science off from philosophy, metaphysics, mysticism, and religion, so I’ll reiterate it. Experimental results can support a theory. Those experimental results have to be repeatable by other scientists. Plus it really helps the credibility of a theory when it is subjected to critical review by other scientists in the field of study (aka “peer review”). Even then, a theory is never considered the end of the scientific endeavor. On the other hand, experimental results can disprove a theory.

A theory that is supported by experimental results and peer review represents our best understanding at that time of how the universe is put together.

“The public has a distorted view of science because children are taught in school that science is a collection of firmly established truths. In fact, science is not a collection of truths. It is a continuing exploration of mysteries.” ~ Freeman Dyson

I hope this sampling of bits of my book gives you some perspective on how the scientific method weeds out ideas that are not supported by real-world experiments. For more on the story of science and gravity, from Aristotle to Einstein (told in plain English) — well, I guess you’d just have to buy the book!

Leave a Reply